Ana Pop Stefanija: A citizen jury for socially acceptable AI systems

Author

Léa Rogliano, Ana Pop Stefanija

When researchers and civil society imagine the future of our cities

In 2023, FARI – AI for the Common Good Institute, in collaboration with Paradigm, launched a grant to its partner research centers to stimulate citizen engagement in Artificial Intelligence (AI), Data and Robotics. Seven projects were supported.

Ana Pop Stefanija, postdoctoral researcher at imec-SMIT, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, experimented with the Citizen Jury method as a way to probe into the ethically and societally acceptable uses of AI proxies for energy distribution in times of crisis. Part of the COOMEP project, it brought together 20 residents of Brussels who jointly discussed and decided on the guidelines and redlines, and the future scenarios of AI and automated decision-making.

In this article, Léa Rogliano, head of FARI’s Citizen Engagement Hub (CEH), asks Ana Pop Stefanija about her experience and feedback. What are we looking for when we open up our research to third parties? What can we expect from such collaborations? What are the best methods for achieving a satisfactory result? The following article is a transcript of this conversation. The CEH’s mission is to stimulate exchanges between researchers and civil society and build a concerted innovation for the common good.

L.R: What does “AI for the common good” mean to you?

A.PS: This means that whatever technology we build, it has to work for the benefit of people. That there are no risks or disadvantages. It also means that it must be built in collaboration with the people it will affect the most. Because they have very specific experiences, I think citizens are best equipped to work on the foundations of technology to avoid potential harmful use.

L.R: Can you give us an example?

A.PS: We had a good example in the Netherlands in 2021, I think, with the scandal that showed that racial profiling criteria had been incorporated into the algorithmic system used to determine whether child benefit claims should be considered erroneous and potentially fraudulent. Many people were wrongly accused of social security fraud. Children were taken away from their families… This system really affected the lives of entire families. The prime minister of the Netherlands had to resign.1 If we build a system to be simply as efficient as possible, but we don’t take into account people’s reality and experiences, we can end up with totally unfair systems.

L.R: Can you summarize the purpose of the citizen consultation you organized for this FARI citizen science project?

A.PS: This citizens jury was part of a larger project, the COOMEP (Coordination mechanisms for the sharing of energy through proxies, from the user to general guidelines) project. The idea was to work on a futuristic scenario in which an artificial intelligence system, possibly through AI-proxies2, would determine how energy should be allocated among households during a general reduction in energy capacity—commonly referred to as a brownout—when there isn’t enough energy to supply all households in Brussels. Delegating highly value-laden, potentially harm-inducing decisions to technological system, unable to fully assess the context and circumstances of use, without human intervention and oversight is exceptionally dangerous. In a situation like this (however hypothetical), we decided to actively engage citizens in the conception and design of this AI technology.

L.R: Can you tell us how the citizen jury was organized?

A.PS: A citizen jury as a tool for soliciting insights from citizens has a very established methodology. It is used when a clear yes-or-no answer is not possible, when the decisions are complex and involve value-judgements, and potentially affecting various communities in various degrees. In short, a citizen jury (or assembly, or a council) is an assembly of citizens who come together to discuss and give recommendation on a particular issue (Smith & Wales, 1999). As such, it is a process and not a one-time event. The aim is to find common ground and form collective recommendations, often to inform policy and decision-making. It should be done in a way that would create democratic spaces for everyday people to grapple with, discuss, and propose solutions to critical issues that (will probably) affect them.

The first step is always to provide participants with knowledge and information (learning phase). Citizens’ juries work on the assumption, as do juries in courts of law, that for the jury to make an informed recommendation, knowledge is required. The second stage is deliberation, during which jurors attempt to reach a decision, guided by facilitators and researchers. The final stage is the formulation of the recommendations.

In this project, we provided knowledge on artificial intelligence systems by bringing in two experts, one computer scientist and one legal scholar. They acted as expert witnesses, who should provide the most important information in a balanced way, tackling on the benefits and the risks of using AI proxies, and providing different perspectives and views. Additionally, we designed the entire process in such a way that at least two weeks passed in between the sessions, so that the jury could reflect and consult the knowledge materials we provided them with.

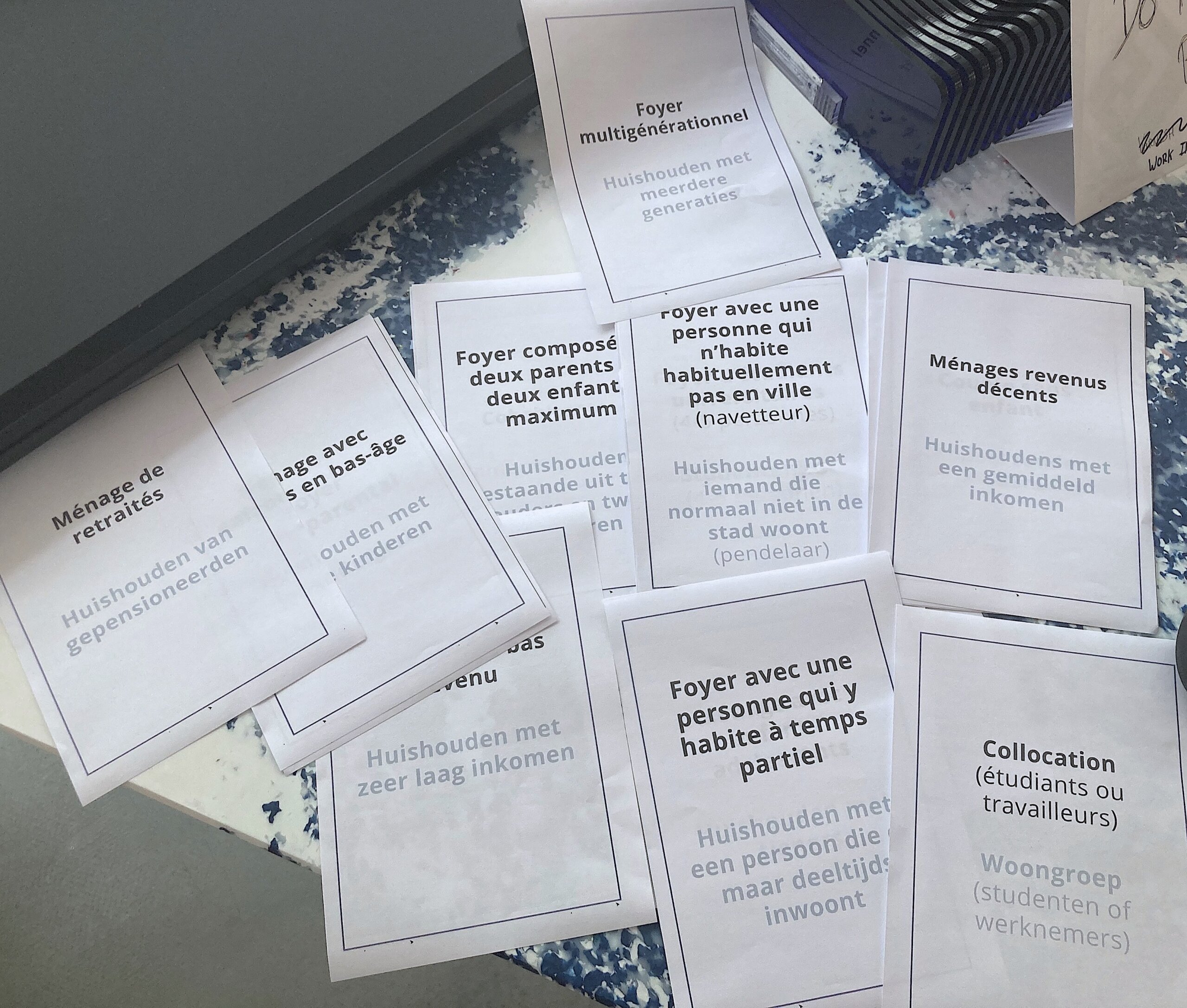

The citizens’ jury must also be representative of the population that will be most affected, in this case the inhabitants of the Brussels-Capital Region. Based on the statistical and demographic composition of the Brussels-Capital Region and using a sortition algorithm, we selected 20 participants from over a hundred individuals who expressed interest through our online and street campaigns. We looked at age, socio-economic status, level of education, place of residence, etc. This work of selection was very meticulous and time-consuming. But as the aim of our research was to see how the people of Brussels would be affected by such technology, a rigorously assembled representative sample of Brussels was required.

L.R: One of the distinctive approaches of your research group, Imec-SMIT, is conducting research in close collaboration with those who either use the technology or are directly affected by how it operates. What have you learned from this citizen jury experience?

A.PS: Doing the citizen jury has been an exceptional research experience. We learned a lot. Often in research, we use what is the most accessible. For instance, we recruit students or policymakers to participate. But in this project, thanks to the citizens’ jury, we reached people who are not easy to connect with. Moreover, we were able to spend a lot of time with them (24 hours in total).

As a researcher, it is important to me to ask for people’s opinions once they have had time to gather knowledge on the subject I’m addressing. In comparison with other quicker methods (e.g., questionnaire, interview), citizens’ juries provide rich and thick qualitative data and insights.

In a citizen jury, participants do more than answer, they experiment, they grasp the technical problems discussed, they reflect and bring their own lived experiences. We asked the participants to think about their own home, then about their neighbors and loved ones, to put themselves in someone else’s shoes. This helps them to consider not just their own needs but also those of the community in situations that might occur to them. And based on that, to deliberate and make their recommendations.

L.R: What were the difficulties?

A.PS: A citizen jury is a long process for the researchers as well as for the participants.

We asked our jurors to commit to three full Saturdays and to remain highly engaged throughout each session. This was the biggest risk: asking for continuous participation.

From the researchers’ side, it was very time and resource consuming even before the jury started. Indeed, the recruitment, sortition, and facilitation process as well as identifying and guiding expert witnesses, should be done by an external party to ensure neutrality. We worked with an external organization taking care of this in consultation with us. The external facilitators also need to understand the matter at hand, so we also had a lot of preparations and meetings there. In total, it took us around 6 months from the initial preparation to the last jury session.

Additionally, for academic institutions, organizing a citizen jury is an expensive process. We provided compensation to the participants, covered the fees of the external organization, and paid for catering services, among other expenses.

L.R: So how long did it take in total?

A.PS: In total around 9 months — 4 months of preparation, 2 months of jury session, and 3 months for analysis (documentations process, doing the transcripts, digitalizing everything) and report write-up.

L.R: Did you achieve your intended goal?

A.PS: We achieved our initial aim, which was to establish the guiding principles for how an AI system should make decisions about energy distribution during a brownout.

The juror produced a set of seven guiding principles. For instance, the system should ensure fairness and cater to everyone’s primary needs. Also, the system should uphold the value of impartiality and ensure the exclusion of discriminatory data.

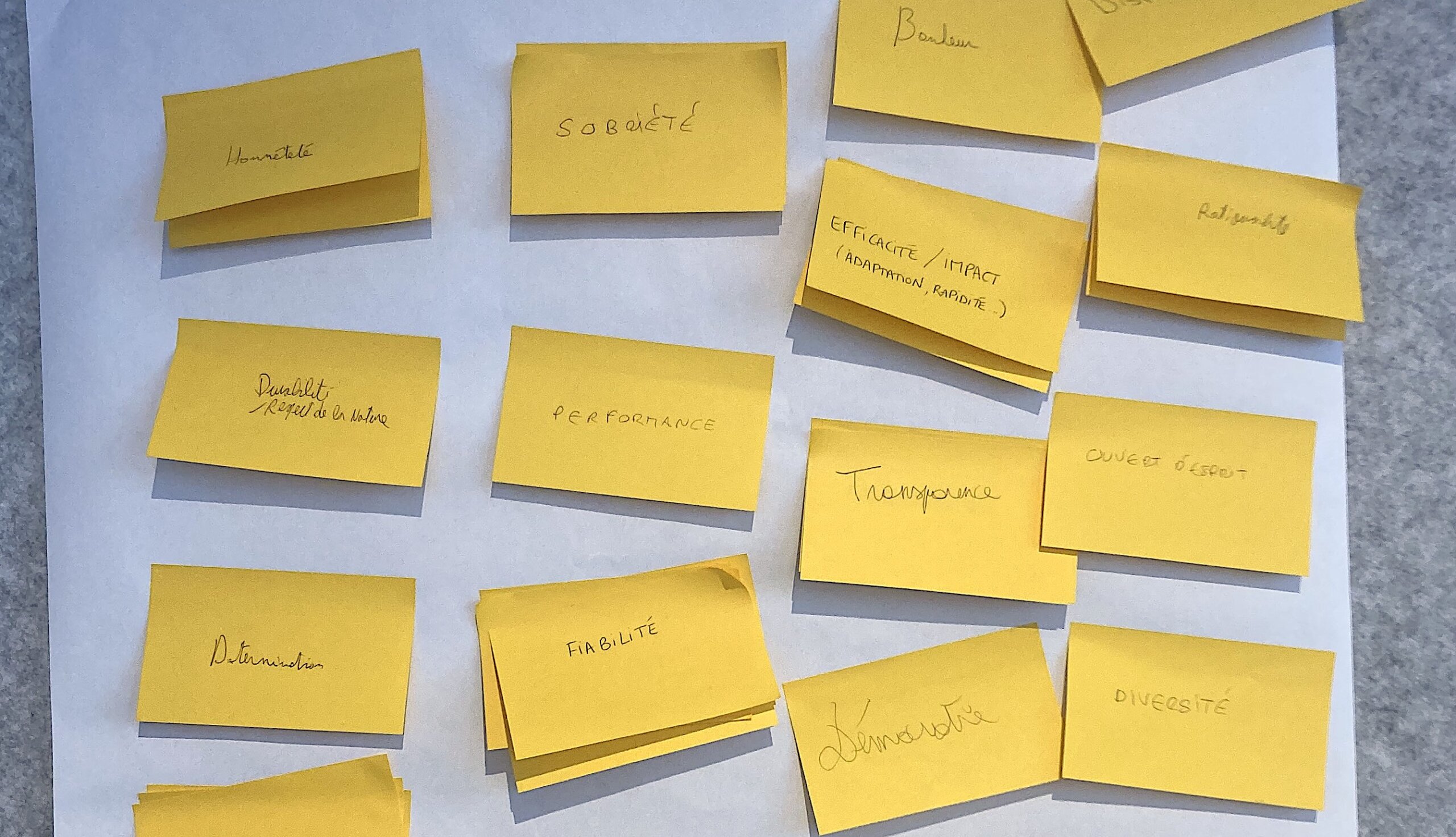

However, the way we designed the jury, in an iterative and knowledge producing way, provided us with the following insights too: a list of identified (29) and prioritized households (5), list of values to guide the technology development and deployment (30 in total) and of most crucial values (5). We also collected future scenarios (dystopian and utopian) of how the jurors envision a future where this system is a reality. So, our insights go beyond the primary goal of simply establishing the guiding principles.

It was intriguing to see the principle of solidarity emerge from all these tough exercises. This revealed the strong level of support present in Brussels. For the participants, this meant that those who don’t need as much energy can give to those who need it the most.

What the citizen jury showed us is that building an AI system is never an easy process. It requires a lot of thought and considering numerous factors. We saw that even humans sometimes struggle to manage all this information and make decisions. Thus, coding the results of this consultation into the algorithm would also be a real challenge. The question then arises: “Should technology decide on such issues?”. Technology is not always objective and does not always know better than us.

L.R: Is your conclusion that technology cannot/should not solve all types of problems?

A.PS: I believe that very complex problems require, precisely because they are complex, the involvement of citizens. I genuinely think that this type of technology needs to be built together and take reality into account. And then, of course, there is a need to test, and test, and test again. It is only afterwards that we can determine if the technology could solve, or should not solve, certain problems. I know that technology and AI are trendy and that today’s societal mantra seems to be about doing things quickly, developing rapidly, but sometimes certain processes require time.

If the project was to continue, it would be very important to use these results to go further, including their dissemination with AI designers and policy makers.

L.R: So, is it a call-to-action?

A.PS: Yes, we think it would be important for policy makers to get acquainted with the conclusions of the citizen jury. And maybe go even further — what about creating a permanent citizen jury on AI that could be used in decision making, policy recommendations, and technology development?

L.R: To conclude our interview, what piece of advice would you give to AI related researchers who want to include citizens in their researches?

A.PS: Do it! Before you even start, think about who you need to talk to. Technology always impacts people, so you must talk with them. Try to think about who you should be talking to in terms of the impact of technology. To whom are we giving a voice? Who are we leaving behind? Are those who will be the most or disproportionately affected taken into account? If not, how can we repair that?

Share

Other news